By: Maria Godoy

By now, you’ve likely heard the advice: If you suspect that you’re sick with COVID-19, or live with someone who is showing symptoms of the disease caused by the coronavirus, be prepared to ride it out at home.

That’s because the vast majority of cases are mild or moderate, and while these cases can feel as rough as a very bad flu and even include some cases of pneumonia, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says most of these patients will be able to recover without medical assistance. (If you’re having trouble breathing or other emergency warning signs, seek medical help immediately.)

But this general advice means anyone living in the same household with the sick person could get infected — a real concern, since research so far suggests household transmission is one of the main ways the coronavirus spreads. So how do you minimize your risk when moving out isn’t an option? Here’s what infectious disease and public health experts have to say:

Physically isolate the person who is sick

If you live in a place with more than one room, identify a room or area – like a bedroom – where the sick person can be isolated from the rest of the household, including pets. (The CDC says that while there’s no evidence that pets can transmit the virus to humans, there have been reports of pets becoming infected after close contact with people who have COVID-19.) Ideally, the “sick room” will have a door that can be kept shut when the sick person is inside — which should really be most of the time.

“It would make sense for the person to just to be in their [contained] area in which we presume that things have virus exposure,” says Dr. Rachel Bender Ignacio, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at the University of Washington and spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America. That way, she says, everyone else can move about the home more freely. A door would also make it easier to keep kids out of the isolation room.

Things get trickier if you all live in tighter quarters, like a one-bedroom or studio apartment, or have shared bedrooms. Everyone should still try to sleep in separate quarters from the sick person if at all possible — “whether it’s one person on a couch, another person on a bed,” Bender Ignacio says.

That said, when multiple people share a small living space like that, “it may be very near impossible to avoid exposure,” says Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. “If you are somebody that has other medical conditions or you’re an advanced age and you’re at risk for having a more severe course [of COVID-19], I do think you should take that into consideration and, if it’s feasible, move out.”

Limit your physical interactions — but not your emotional ones

Even as you try to limit your face-to-face interactions with the sick person, remember, we all need human contact. Try visiting via text or video options like Facetime instead. Old-fashioned phone calls work too.

Whenever you are in the same room together, the CDC recommends that the sick person wear a cloth face covering, even in their own home. In practice, however, Adalja notes that “it can be uncomfortable for someone who’s sick to wear a mask all the time in their own house” — hence, another reason to limit those interactions.

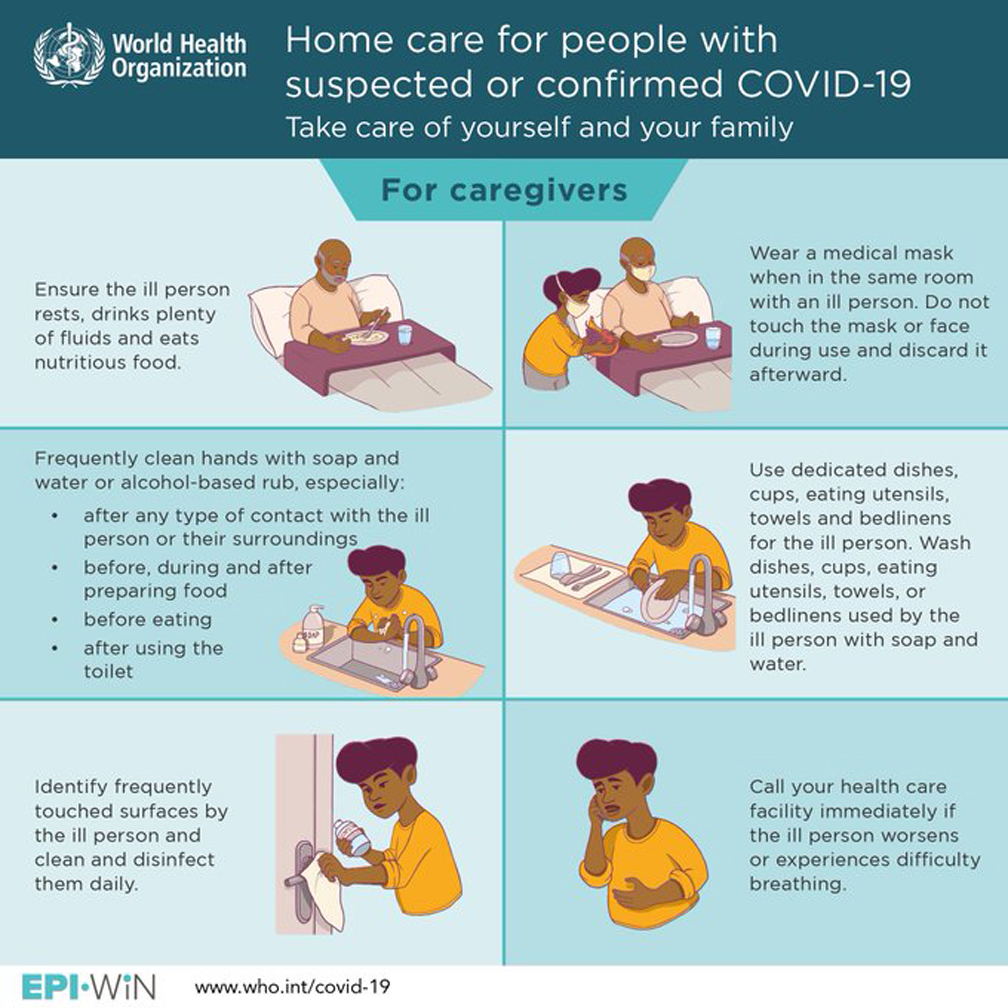

Just make sure to wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water for at least 20 seconds after every visit with the ill person.

Consider yourself quarantined, too

Bender Ignacio says if one person in the household is sick, everyone else in the household should consider themselves as possibly having asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic infection, even if they feel fine.

That means you should quarantine yourselves at home, too, she says, and ask a friend or neighbor to help with essential errands like grocery shopping — so you don’t run the risk of exposing other people in the store.

“The important consideration is that the entire house should be considered potentially infected for up to two weeks after people who are ill stop having symptoms,” Bender Ignacio says. It’s important to understand “that anybody leaving that house also has the possibility of bringing the virus out.”

If others in the household do get sick, one after the other, that two-week quarantine should restart with each illness, she says – which means you all could end up quarantined together for a long time.

If you have to share a bathroom …

The CDC says anyone sick with symptoms of COVID-19 should use a separate bathroom if at all possible, but for many of us, that’s not an option. If you do share a bathroom, the CDC advises that the caregiver or healthy housemates not go into the bathroom too soon after it’s used by a person who has the virus.

“The hope is that with more time, if the patient was coughing in the room, fewer infectious droplets would remain suspended in the air,” explains Dr. Alex Isakov, a professor of emergency medicine at Emory University and one of the creators of Emory’s online tool for checking for COVID-19 symptoms at home. “It would help if you could ventilate the bathroom by opening a window, or running the exhaust fan, if so equipped.”

If feeling well enough, experts say, the person who tested positive for the virus should disinfect the bathroom before exiting, paying close attention to surfaces like door knobs, faucet handles, toilet, countertops, light switches and any other surfaces they touched. If they can’t do that, then the healthy housemate should wait as long as feasible before entering to disinfect, then wash their hands thoroughly afterward. And — this is key — each person in the household should use only their own frequently laundered towel.

Bender Ignacio says it wouldn’t be a bad idea to try to remove all the bottles and lotions people tend to keep in the bathroom, so you can minimize the number of surfaces you have to disinfect in there. One idea: Everyone in the home might carry the items they’ll need to use in the bathroom with them in a caddy, and remove them when they exit.

Handling food and dirty dishes

The whole goal of isolating a sick person is to minimize the areas they might be contaminating, so having them cook their own food in a shared kitchen should be considered a no-no, Adalja and Bender Ignacio agree.

“You just want to limit that person’s interaction with other people and around common-touch surfaces” like the kitchen, says Adalja.

Instead, someone else in the house should prepare food for the sick person and take it to their isolation spot. The CDC recommends using gloves to handle and wash their dirty dishes and utensils in hot, soapy water or in the dishwasher. Make sure to wash your hands thoroughly after handling the used items.

Parenting challenges

Of course, Facetime chats aren’t likely to cut it if you’re the parent of a young child who is sick. “I think that it’s probably unfeasible to mask a sick child in their own home,” says Bender Ignacio, adding, “If the child is the one who’s sick, they need physical contact. That’s important.”

Keeping small children away can also be difficult if it is the parent who is sick. “If you have a child and you have a partner and that child is satisfied with the partner’s hugs, then that’s great,” she says.

But “if the sick person is the only caregiver, then there has to be physical interaction,” she says. “And I think we should be reassured to some extent that even though children are as likely as adults to get sick, we know now they’re much less likely to get severe disease.”

As with most things when it comes to parenting, “you just do the best you can,” she says.

Laundry

“The good thing about the coronavirus is that it is easily killed by soap and water,” says Bender Ignacio. The CDC advises washing clothes and other fabric items using the warmest water setting appropriate. The agency says it’s fine to wash a sick person’s clothes with everyone else’s — and make sure to dry items completely. Wear disposable gloves when handling the sick person’s laundry, but don’t shake it out first, the CDC says. When you’re done, remove the gloves and wash your hands right away. And don’t let the sick person’s clothes linger on the floor, says Bender Ignacio.

“Make sure that laundry takes the shortest line between the hamper and the washing machine.” Consider putting soiled clothes directly in the washer. If you use a hamper, it’s a good idea to use a washable liner or a trash bag inside of it, says Bender Ignacio. Otherwise, she advises wiping down the hamper with soapy water afterward.

Disinfecting

Commonly touched, shared surfaces in the house — such as tables, chairs, door knobs, countertops, light switches, phones, keyboards, faucets and sink handles — should be disinfected daily with a household disinfectant registered with the Environmental Protection Agency, according to the CDC. (It doesn’t have to be spray bleach, or a fancy product — Comet disinfecting bathroom cleaner, Windex disinfectant cleaner, and many other easily found products are on that list.) The agency advises wearing disposable gloves when disinfecting surfaces for COVID-19.

However, unless you have to change soiled linens or clean up a dirty surface, try not to go into the sick person’s room to clean, the CDC says, so you can minimize your contact. Give them their own trashcan, lined with a paper or plastic bag that they can then remove and dispose of themselves if possible. Use gloves when taking out the trash and wash your hands right after you remove the gloves, the CDC says.

Protecting vulnerable people in the home

Recovering from COVID-19 at home poses particular challenges if someone else in the home is at higher risk of developing a severe case of the disease. That’s of particular concern in multigenerational households. It would probably be safest for that at-risk household member — say, a grandparent, or person with cancer or an autoimmune disease — to move someplace else temporarily, until everyone else in the family is symptom-free, says Adalja.

However, moving out isn’t an option for lots of people, and there’s also the chance that the at-risk person might already be infected, in which case they could potentially transmit the virus to anyone else they moved in with, notes Bender Ignacio.

“The best option is to essentially find the safest room or rooms in the house for the most vulnerable people and then exclude everyone else from those rooms,” she says. “Visit those people with meals in their room if there is a high concern.”