By LEE GAINES

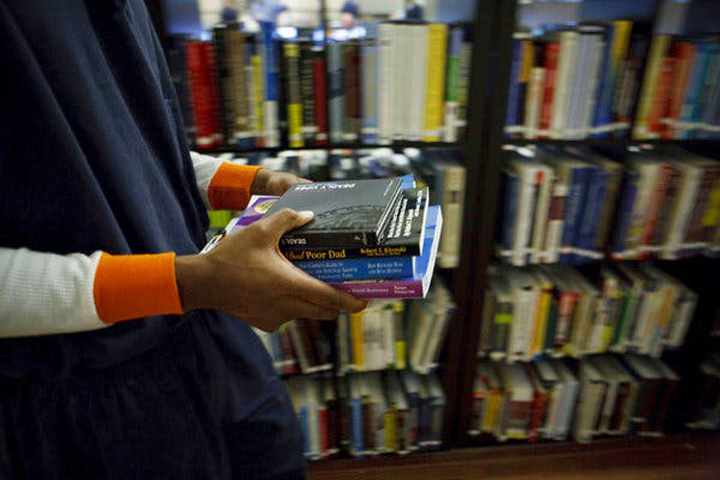

Michael Tafolla says the books he read in prison helped him understand how he had landed there in the first place. He remembers one especially eye-opening title: Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant.

“The main topic of this book is how a human being is reduced to an action that’s perceived by others to be wrong,” Tafolla says. “And therefore he is not a human being, but he is a walking, talking, breathing crime act.”

Tafolla was released from Danville Correctional Center in 2018. Not long after, in January 2019, officials at the Illinois prison censored Illegal and about 200 other books, removing them from the library of a college-in-prison program. Officials were concerned about “racially motivated” material, according to documents obtained by Illinois Public Media.

Experts say this is just one example of the kind of arbitrary book censorship that incarcerated people face nationwide — censorship that can make it harder to get an education behind bars.

“It’s so important for people who are in prison to be able to have access to materials that give them hope and a reason to want to be part of society again, to want to engage, to see the future,” says Rebecca Ginsburg of the Education Justice Project. She says she was shocked and angry when she learned the books had been removed from her program’s library at Danville.

A recent report from PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for free expression, found that book censorship in U.S. prisons represents “the largest book ban policy in the United States.” And while censorship guidelines vary in different prison systems, the restrictions “are often arbitrary, overbroad, opaque, [and] subject to little meaningful review.”

In Kansas, state prisons don’t allow Angie Thomas’ young adult novel, The Hate U Give, or Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye — but they do allow Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

Texas prisons have censored Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, which won a Pulitzer Prize; New Hampshire barsAlice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones; and Florida has censored multiple books about learning Arabic, Japanese and American Sign Language.

A 2013 report from the RAND Corporation found that getting an education in prison decreases the likelihood someone will return after they’re released. The report also found that for every $1 spent educating someone in prison, taxpayers save $5 on reduced reincarceration costs.

“A fine line” for prison officials

Diana Woodside, director of policy and legislative affairs for the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, says that of course, some reading material should be banned from prisons.

“There’s a lot of how-to books and how-to articles in magazines, such as how to strangle someone with your bare hands — that was an actual article in a very popular men’s magazine. … There’s also writings that are specific for inmates: how to escape from handcuffs.”

Woodside points to two common standards for evaluating publications: “Do they pose a potential threat to the security of the operation of the prisons? Or do they contain nudity or sexually explicit materials?”

Some publications clearly violate those standards — but Woodside acknowledges there’s a large gray area.

“There’s a fine line between, you know, imposing our own personal judgment on the quality of the content of that book and making really sound, rational decisions to keep our facilities safe.”

One of those gray areas is nudity. Woodside says prison officials in Pennsylvania struggle over whether to allow certain graphic novels, specifically from Japan.

“It’s called manga. [It] really has really vivid graphic pictures that include sex acts and nudity,” she says. Officials tend to deny a publication that has nudity if it’s intended for “sexual gratification,” Woodside says. But when it comes to manga, that’s not always an easy call.

“Is it better to allow it in, or to not allow it? Does it really impact the atmosphere of the institution? I don’t know the answer to that,” Woodside says.

“There’s a lot of inconsistencies. I would love to see a standard for nudity.”

Materials that “affirm their humanity”

Rebecca Ginsburg of the Education Justice Project says race and black history were common themes among the books Danville Correctional Center officials removed from her program’s library.

“That sent a message to our students, who are predominantly African American men, about the continued power of the prison administration over their lives,” she says.

In fact, according to PEN America, prison systems frequently censor books about race and criminal justice on the grounds they could be disruptive.

But former EJP student Michael Tafolla says that’s not the effect the books had on him.

“[These books] helped me understand why so many of us end up in the predicament of this vicious cycle of mass incarceration,” he says. “And it showed me how we could combat it not by breaking laws, but by empowering our people to be so much more than what we’ve been reduced to.”

After leaving prison, Tafolla, 39, started working with a nonprofit that helps young people on Chicago’s South Side.

Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, says Tafolla’s story illustrates an important point: Denying incarcerated people broad access to reading materials doesn’t just interfere with their education.

“We’re depriving prisoners of materials that they desperately want and need to affirm their humanity, to help them rehabilitate themselves, to occupy their minds and their hearts while they’re in prison,” she says.

“Changing culture is very, very difficult”

After a public outcry, the books were returned to the EJP library last summer. Then, in the fall, the Illinois Department of Corrections revised its publication review policy: It now places censorship decisions in the hands of a centralized committee, instead of individual prison officials. “Illinois is actually an example of a state that is actually trying to get it right,” Caldwell-Stone says.

She says the policy revision looks like an improvement, but only “if it’s applied as it’s written, and it’s implemented with the idea that what is needed is to provide a means for inmates to educate themselves.”

In Pennsylvania, Woodside acknowledges that her agency’s policy is “very vague and open to interpretation.” She says she would like to see more training offered to corrections staff who evaluate the publications that enter prisons — training that encourages thoughtful censorship decisions and helps staff members understand the importance of the First Amendment to incarcerated people.

But there’s likely still a long road ahead.

“It’s easy to change our written policies. What’s hard to change is the culture of: This is how we’ve always done it, and we’ve always denied it, so why not continue to deny it?” Woodside says.

“And changing culture is very, very difficult.”