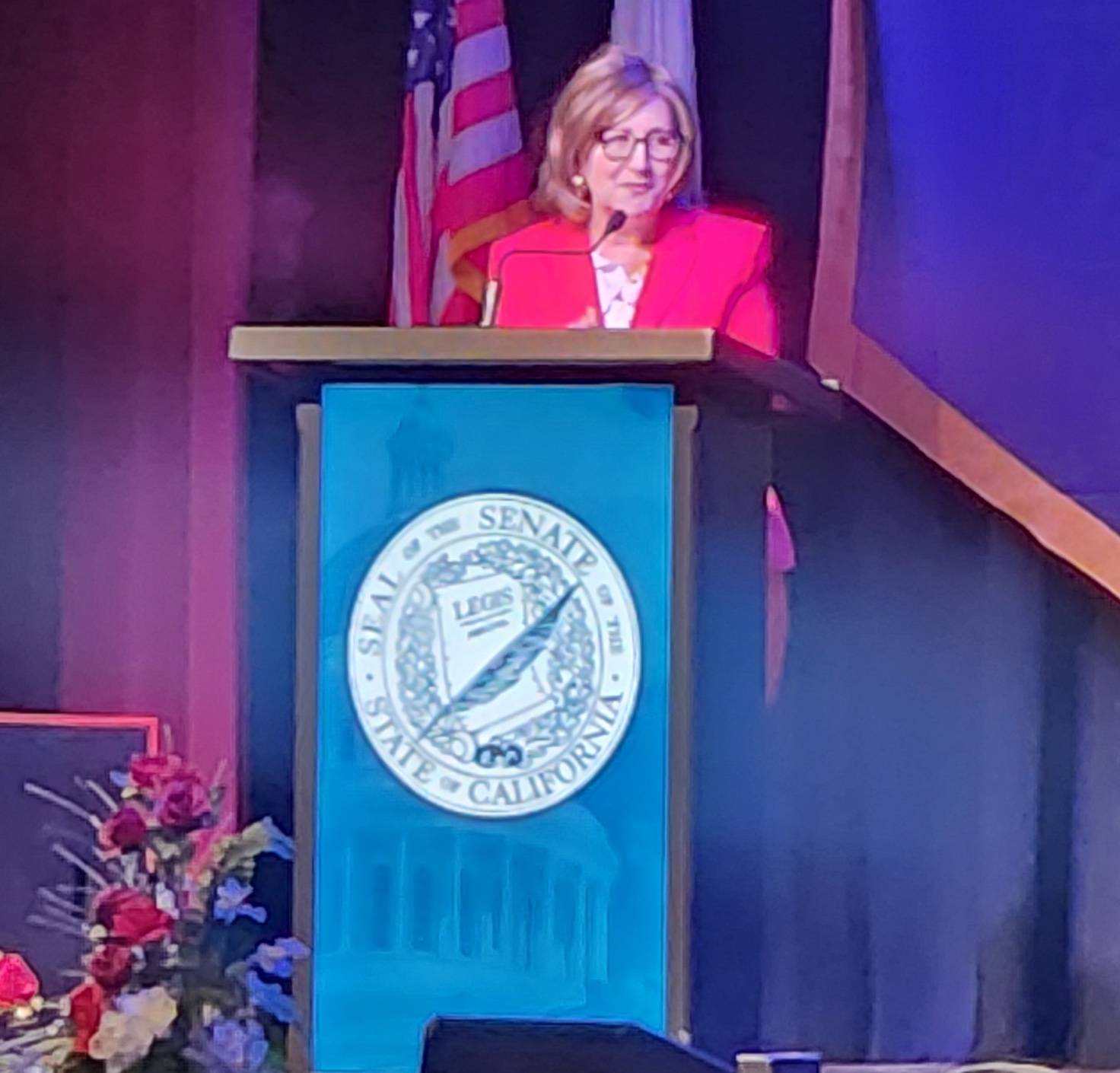

Linda Hart, Founder and Executive Director, African American Health Coalition

San Bernardino, CA — Linda Hart’s advocacy work began long before she founded a nonprofit or helped shape statelegislation.

It began, she said, when she was a teenager navigating racism firsthand while helping integrate a San Bernardino high school in the 1970s.

“We were met with hostility and racism,” Hart said. “We actually had to end up having the National Guard come down and take us to class.”

Hart, now the founder and executive director of the African American Health Coalition, said those early experiencesshaped her understanding of advocacy; not as a career path, but as a necessity.

“You would think this happened down in Alabama,” she said. “No, it happened right here.” In the classroom, Hart said, racism was not always overt, but it was persistent.

She recalled a history teacher discouraging her from pursuing law.

“I always wanted to be a lawyer,” Hart said. “And I had my history teacher tell me to pick another line of work because that just was not going to happen.”

Rather than deterring her, Hart said moments like that pushed her deeper into advocacy.

“He didn’t motivate me in the sense that, ‘Oh, you can do it,’” she said. “But it did motivate me to start my advocacy work, which was even greater.”

By the 1980s, Hart’s focus expanded to environmental justice after parents discovered arsenic contamination linked to illegal dumping at a local high school.

After organizing parents and pressing state agencies to investigate, officials fenced off a contaminated section of the campus.

“They fenced it off for the next hundred years,” Hart said. “I go by, and there’s still a fence around that little section.”

Hart’s advocacy later moved into public health during the height of the HIV and AIDS crisis, when stigma often prevented open discussion in Black communities.

She co-founded Brothers and Sisters in Action, intentionally meeting people where they were.

“We would go to the churches, the barbershops, the beauty shops,” Hart said. “We even set up vendor tables in nightclubs.”

Her work took another turn after a family member died by suicide, revealing what Hart described as a lack of culturally responsive mental health advocacy.

“There was no advocacy work in mental health,” she said. “So I said, ‘Let me transition over into that.’”

That shift eventually led to the creation of the African American Mental Health Coalition, later renamed the AfricanAmerican Health Coalition to reflect the interconnected nature of physical, mental and social well-being.

“I found that there were disparities across the board,” Hart said. “Not just with mental health, but with our health in general and what affects our mental health.”

In 2011, Hart helped create state legislation recognizing African American Mental Health Awareness Week.

Assembly Bill (AB) 150 was signed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“That was a piece of legislation that we created under the African American Health Coalition,” Hart said.

Over the years, Hart’s coalition trained dozens of community outreach workers who served thousands of residents across San Bernardino and Riverside counties.

“We served close to 10,000 people,” she said. “Specifically targeting the African American community at the time.”

Outreach extended to apartment complexes, homeless encampments and street-level engagement, often paired withfood distribution, legal clinics and educational opportunities.

“In order to have good mental health, you need to be fed,” Hart said. “The kids need to be fed. One less stressor in the family.”

Hart’s advocacy is also shaped by lived experience. She spoke candidly about navigating the mental health system for her own son.

“Love cannot cure mental illness,” Hart said. “I understand because I was there once.”

Those experiences led her to advocate for stronger mental health response systems, including police-behavioral health co-response models.

Hart said she has worked directly with law enforcement to push for training and accountability.

“Every department should have someone from behavioral health,” she said. “People get shot and killed during mental health crises when there’s no training.”

Throughout her career, Hart said she has drawn guidance from elders and organizers who came before her, includinglongtime community activist Frances J. Grice, whom Hart has fondly described as a mentor.

Today, Hart continues to host parenting workshops, suicide prevention trainings and legislative advocacy days that take Inland Empire parents to Sacramento.

“A lot of people don’t know how to talk to legislators,” she said. “So we teach them.” For Hart, the work remains rooted in education and self-determination.

“No one can take my history away from me because it’s part of who I am,” she said. “Whenever there’s a challenge, that’s an opportunity.”