By Claudia Grisales

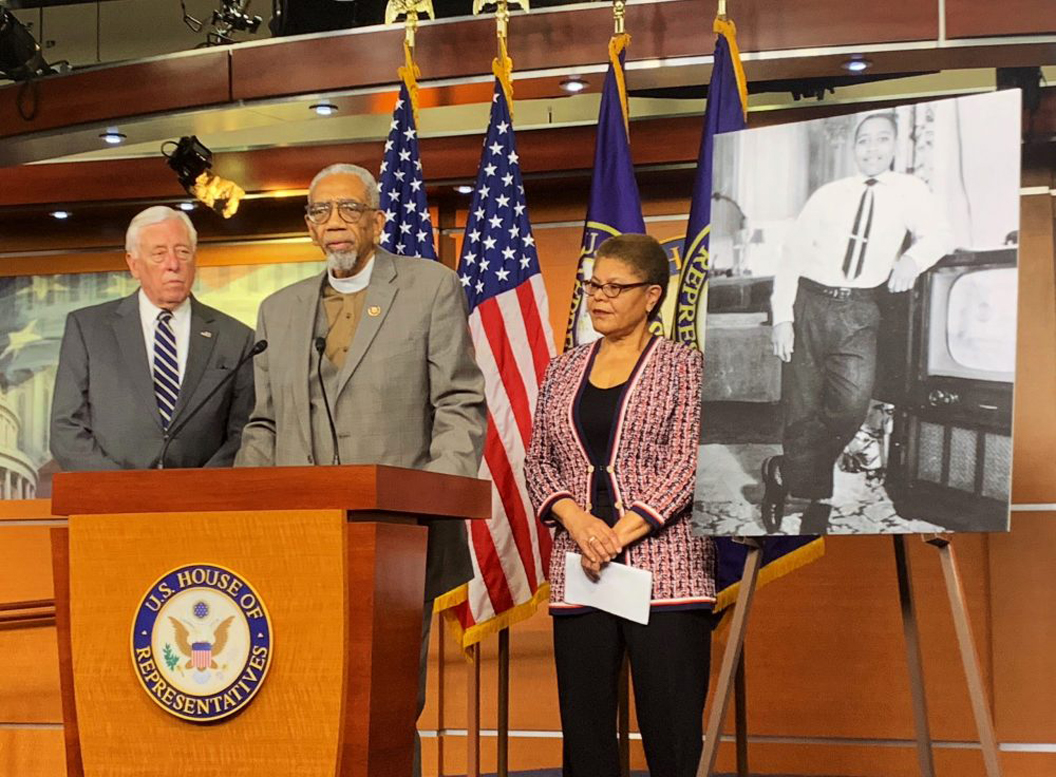

Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill., speaks during a news conference about the Emmett Till Anti lynching Act on Wednesday on Capitol Hill. He stands beside a photo of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American who was lynched in Mississippi in the 1950s.

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

With supporters calling it more than 100 years in the making, the House of Representatives overwhelmingly approved legislation on Wednesday that makes lynching a federal hate crime for the first time in U.S. history.

The Emmett Till Antilynching Act was approved in a vote of 410-4. Three Republicans and one independent representative voted against it.

Advocates say there have been more than 200 attempts to pass the legislation in the past, and the latest effort has been in the works for nearly two years.

“This act of American terrorism has to be repudiated,” Illinois Democrat Bobby Rush, who sponsored the legislation nearly two years ago, told NPR. And “now it’s being repudiated. It’s never too late to repudiate evil and this lynching is an American evil.”

While there are no recently recorded lynchings, sponsors say, the House bill remains critical.

The legislation was named for a 14-year-old Chicago teenager who was lynched in the 1950s during a visit to see relatives near Money, Miss. His body was recovered from the Tallahatchie River.

California Democratic Rep. Karen Bass, a co-sponsor of the House bill, says although the legislation touches on a difficult period in U.S. history, it also stands as a reminder of the hate crimes that continue today.

For example, she noted that a Mississippi memorial in Till’s honor has been vandalized several times. Last year, cameras were installed and the memorial was covered in bulletproof glass to prevent new attempts of vandalism.

“Even today, periodically, you hear news stories of nooses being left on college campuses, worker locker rooms, to threaten and terrorize African Americans — a vicious reminder that the past is never that far away,” Bass said.

Reps. Louie Gohmert of Texas, Thomas Massie of Kentucky and Ted Yoho of Florida and the chamber’s lone independent, Justin Amash of Michigan, voted against it.

The U.S. saw more than 4,000 cases of lynching between the late 1800s and the 1960s, according to the Montgomery, Ala.,-based nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative. Many of those cases involved black men.

“We often like to only talk about only the glorious parts of our history, and it’s difficult for us to hear some of the ugly parts,” Bass, the co-sponsor, said. “But it is important that we do hear and understand our history in full.”

Rush said he first filed the legislation in June 2018 after hearing from the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who asked the lawmaker if he knew that lynching wasn’t a federal crime. Rush said he did not.

But Rush says his journey to sponsoring the legislation probably started long before that.

As a child, Rush said his mother sat him and his four siblings around a table in their Chicago home to share images of Emmett Till. Jet magazine published graphic photos shared by the teen’s mother of Till’s body in a casket to illustrate the painful legacy of lynching.

“That atrocity has been really something that has been with me, that’s a part of who I am,” Rush said in a struggling, soft-spoken voice, his vocal cords previously damaged as a result of an illness. “Emmett Till in that casket launched the civil rights movement in America.”

Rush’s mother told her children that Till’s story was why they left their home state of Georgia, and moved to Chicago instead.

The Senate passed similar anti-lynching legislation, led by California Democrat Kamala Harris, for the first time in December 2018. However, the legislation failed to gain traction in time for the end of the legislative session that year.

So, in February 2019, Harris introduced and gained passage again for her anti-lynching bill for the new legislative session. But since the House bill is titled differently, now the Senate must take up Rush’s measure in order to send it to the president’s desk.

Harris lauded the news of the House passage on Wednesday.

“It’s about time that the United States Congress take this issue up,” Harris told NPR a day before the vote. “It represents the thousands of lives that were the subject of extreme violence and criminal activity in saying — finally — that it was a crime that was committed against those folks, and it should never be repeated. So it is one of the most significant pieces of legislation that we could ever address.”

Lawmakers have said they hoped the Senate could take up the House measure during the final days of Black History Month, but that remains to be seen. The Senate returns Thursday after a one-day recess for party retreats.

But lawmakers remain hopeful the Senate can pass the House measure in the near future and send it to President Trump’s desk.

“I’m very proud of that. I helped negotiate it and I’m grateful for the leadership of the House and the House members who were part of it. It’s really historic,” New Jersey Democratic Sen. Cory Booker, who co-sponsored the Senate measure with Harris, told NPR.

In terms of the timing, Booker said, “It’s Black History Month, it’s been too long, and the time to do right is always right.”

On Wednesday, a White House official told NPR that Trump is expected to sign it.